Do you always think logically? Always make rational decisions.

Probably not. Even if you think you do.

“Prospect Theory” in economics says people make decisions based on the potential value of losses and gains, rather than the final outcome.

Under the Prospect Theory, investors make real world choices based on “Heuristics”… mental shortcuts… “rules of thumb”… that may or may not give us accurate results, but save us time in thinking up solutions.

Unfortunately, every rule of thumb that saves us time in making decisions has the potential to bias our decisions.

Let’s look at some of these cognitive biases…

1. Framing

We all have our personal information filters. Our filters create a “frame” for the pictures we see. The Frame then influences how we see the picture. In short, the way we ask a question influences our answer to the question. We draw different conclusions from the same information… depending on how that information is presented.

We all have our personal information filters. Our filters create a “frame” for the pictures we see. The Frame then influences how we see the picture. In short, the way we ask a question influences our answer to the question. We draw different conclusions from the same information… depending on how that information is presented.

Our aversion to a particular risk depends on how a question is framed. A question about how much profit you might make (positive frame) makes you more likely to pick secure options. The same question framed in terms of how much you might lose (a negative frame) actually makes you more likely to gamble.

The positive nature of the first question influences your desire for security. The negative frame of the second version makes you more likely to take risks.

So as an investor, do you focus on the profit potential of a deal… or the risk of loss. Your focus actually subtly influences your risk tolerance… whether you know it or not.

2. Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency we have to favor information that confirms our beliefs. We gather, interpret and remember information selectively. And we interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting our existing preconceptions.

Have you ever bought a new car…. and then suddenly you see that new car EVERYWHERE? You simply never noticed it before, because you weren’t looking for it.

When a real estate investor is pulling comparable sales for a neighborhood, we have a tendency to only notice the ones that support our existing idea of a fair price. We overlook or explain away the sales that don’t conform to our notion of the right price. When an appraiser finds different comps… ones that don’t support our preconceived notion… we are shocked and angry.

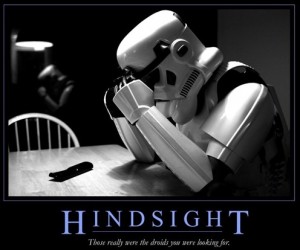

3. Hindsight Bias

This is the “I knew it all along” effect. We think things that have already happened are more predictable than they were before they took place. Our brains lie to us to tell us we understood a situation better than we did.

When another investor buys a house and loses money, we tell ourselves that we were smarter than him, because we knew that house was a loser…. Even if we were bidding on that house and wanted it at the time.

4. Self-Serving Bias

The Self-Serving bias is when we take credit for our success… but blame our failures on outside factors. The student credits her good grade on a test to her intelligence…. but a bad grade is the teacher’s fault for not teaching well.

As investors, we credit ourselves for recognizing the great deal that nobody else saw. But if the deal goes bad… we can easily find someone or something else to blame. We protect our self esteem by taking credit and assigning blame.

5. Anchoring

Anchoring describes our tendency to rely on one piece of information when making a decision… even if that information is completely unrelated to the decision.

If I ask two investors to write down the last two digits of their social security number and then ask them to bid on something random (and they don’t know the inherent value), the person with the higher social security number will bid at least 60% higher than the one with the lower number. The “anchor” adjusts our notion of value… even when it is obviously has nothing to do with the value of some unrelated item.

Anchoring is often seen when a potential buyer finds out what a flipper paid for the house at the auction. They “anchor” to this price and adjust upward to pay what they think is a “fair profit.” The price the seller paid is completely irrelevant… the only question that matters now is what the house is worth. If the buyer wanted the best price… they should have gone to the auction and taken all that risk. But buyers who anchor to that earlier purchase price can overlook the cheapest house in town because of their bias.

6. Endowment Effect/ Loss Aversion

The Endowment Effect is when people demand more to give up an object than they would be willing to pay to acquire it.

If I give you tickets to the NCAA Final Four, your selling price once you are holding the tickets is going to be a multiple of what you would be willing to pay for those tickets.

Loss Aversion is related to the Endowment Effect. It refers to our tendency to strongly prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains. Losses are twice as powerful psychologically as gains.

Would you rather get a $5 discount… or avoid a $5 late fee? Most people pass on coupons all the time- but avoid a late fee like the plague. The exact same difference in price has a very significant effect on our behavior.

7. Sunk Cost Effect

Once you’ve made an investment, your cost has already been incurred and can’t be recovered. Your past expenses are irrelevant to future investing decisions. The amount we paid for something should not affect a rational future decision… but it does for most of us.

Ever sit through a bad movie because you already paid for the ticket? Rationally, you’ve already incurred that expense. Now your choice is between suffering through a bad movie OR walking out to do something more enjoyable. When did you last walk out of a bad movie?

Investors buy and rehab a house and then put it on the market with no response. They know the price needs to be lowered…. but they also know what they have invested in the deal and want to recover those sunk costs. Irrational. But we do it all the time.

8. Irrational Escalation

Irrational Escalation describes people making irrational decisions to justify rational actions already taken.

Investors will increase their investment in a decision despite new evidence suggesting the decision was wrong.

Bidding wars are a great example of this. Bidders who drop out at their predetermined maximum bid are being rational. Bidders who end up paying a lot more than they wanted, to justify the time spent researching the auction and because they don’t want to get pushed around… not rational.

9. Normalcy Bias

Normalcy Bias refers to people underestimating the possibility of a disaster. People with a normalcy bias assume bad things won’t happen simply because they haven’t happened before. We interpret warnings optimistically, using ambiguous information to infer a less serious situation. In other words, we prefer the rosy status quo.

An investor who buys his first house with a sinkhole will be shocked…. all those other houses without a sinkhole conditioned him to believe such a disaster was impossible.

On a broader scale, the normalcy bias caused the current foreclosure wave. Back when credit was plentiful, people with no income or assets could build spec houses… and nobody thought that was a problem. The real estate market was booming, and nobody could see an end in sight…. because the status quo was a booming market.

Today REOs, foreclosures and short sales dominate the real estate market. But soon that will all change, and an investor with a normalcy bias will miss the next boat.

So what “irrational” biases impact YOUR thought process? Please comment below or share this post!